What goes into creating habitat and biodiversity hotspot maps of the vast ecosystem of Malawi’s long, narrow, biodiverse Great Lakes region? Start with four CRC staff members, five diligent extension officers working for the nation’s Department of Fisheries, three conscientious field assistants, one month in the field, four distinct lake habitats, eighteen communities, 36 focus groups, 36 individual maps, 30 workshop participants, countless hours of travel, information gathering and data analysis, a strong commitment from the Malawi FISH Project team, and local communities generously sharing their local knowledge.

CRC’s Glenn Ricci, Coastal Manager, Daniel Jamu, FISH Deputy Chief of Party, Cathy McNally, post-doctoral fellow, and graduate student Bill Favitta (Master’s of Environmental Science and Management, CELS) spent most of July and part of August working hand in hand with the local Malawian field team. Together they gathered and processed information from local shoreline communities and scientists in Malawi, using GIS technology to map the massive freshwater lakes. Their work is part of the United States for International Development (USAID)-funded Fisheries Integration of Society and Habitats Project (FISH). CRC is providing technical expertise developing sustainable fisheries management plans for the five-year biodiversity and climate change adaptation project led by PACT, an international NGO. It is CRC’s first foray into a freshwater environment.

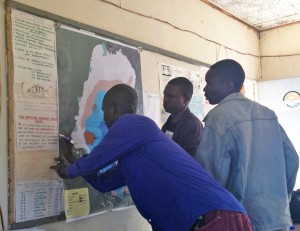

The CRC team started with a foundation of local ecological knowledge amassed earlier in the year via a suite of participatory rapid appraisal (PRA) methods carried out by the in-country field team comprised staff from PACT and the Department of Fisheries. In each community, the team convened focus groups engaging the village chief, Beach Village Committee Members, fishermen, women processers and fish traders in mapping exercises to compile fish species-specific information as well as habitat knowledge best mined from local people. “The field team started with a blank piece of paper that had only an outline of the lake, and asked the community members to share their perceptions and insights with them,” McNally said. For example, community members know their lakes the way others know their city block. Where are the rocky areas, the deep areas, important aquatic vegetation? What habitats do the fish harvested by artisanal fishers use for mating, nursery grounds, and adult feeding areas?

The habitat information and species-specific life-stage habitat requirements collected from the communities were compiled and used to create a number of GIS data layers. Favitta took the data synthesized by the field team for each lake and created eight separate maps, a habitat and biodiversity hotspot map for each lake. The resulting maps were validated by the communities during follow-up visits and were corroborated and augmented with additional information provided by local fisheries experts in a two day workshop.

“We went out to make links between fisheries species and habitats and identify where the main biodiversity hotspots are in each lake,” Favitta said. For two of the more remote lakes—Chiuta and Malombe—this was the first effort to map their habitats. “The local residents and fisheries extension officers were really excited to be a part of it,” he said. The local knowledge was crucial.”

And the information they shared enriched the work. “The amount of primary data collected from the local communities to create these maps and document their perceptions of the greatest threats to their resources added a greater level of meaning to the work, and validated and expanded upon other research conducted in the region”, McNally said.

The project team also asked the communities to describe any efforts that they had taken to date to mitigate the most pressing threats to the fisheries and reflect upon intrinsic strengths that the FISH project could build upon.

“I think the comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach, looking at the issue through multiple lenses—biodiversity, climate change, co-management, community resilience—also set the work apart,” Favitta said.

“There was a lot of enthusiasm exhibited by the local communities and fisheries extension staff,” McNally noted. “It was informative and fun to watch the fisheries extension staff employing different techniques to draw out the information from the communities and exciting to see them take full ownership of the PRA activities and follow-up validation visits.”

Scientists and fisheries researchers then reviewed the maps and data and provided feedback during a stakeholder workshop. Favitta eventually pulled together all the information gathered, digested and validated to build comprehensive GIS-based maps of the four lake ecosystems. Favitta, Ricci, McNally and the field team then continued sharing that feedback with the local communities. So far, the in-country project team has visited 13 of the 16 communities involved.

“I was surprised to see just how closely the local ecological knowledge gathered from the communities overlapped with the information shared by the local fisheries scientists, and hope that this encourages others to meaningfully involve local community members,” McNally said.

Working closely with the communities was a highlight for Favitta. “It provided a great perspective on the people that will be supported by the FISH project.”

Based on the accuracy and breadth of information gathered, the FISH project will be able to go into the communities and propose joint practical solutions to the threats identified by the communities. For example, one idea to help mitigate the pervasiveness of illegal fishing is to create “bush parks’ in the lakes as a deterrent. A bush park is a framework built in the water and filled with woody debris that eventually becomes covered in algae, which attract fish for feeding. “It serves as both a deterrent for illegal fishing activities while also boosting the local fish resources. These help protect local community’s waterways and resources for the local people,” Favitta said.

Back in Rhode Island, the CRC team is writing up the findings, which will highlight the community’s input and ideas and help to guide project activities going forward. The next stage of the project will use the maps and data to determine what interventions, such as “bush parks,” should be pilot tested and perhaps scaled up during the life of the project.

“It’s one step in the dialogue of what kind of project interventions can be pursued with the local communities to address the greatest threats facing them,” McNally said.